Dive Brief:

- Consumers struggle to identify and properly dispose of compostable materials, according to a newly released report from BPI and Closed Loop Partners’ Composting Consortium. The partners conducted a digital survey with 2,700 participants to determine how different labeling and design techniques influence consumers’ perceptions of compostable and non-compostable packaging across 10 categories.

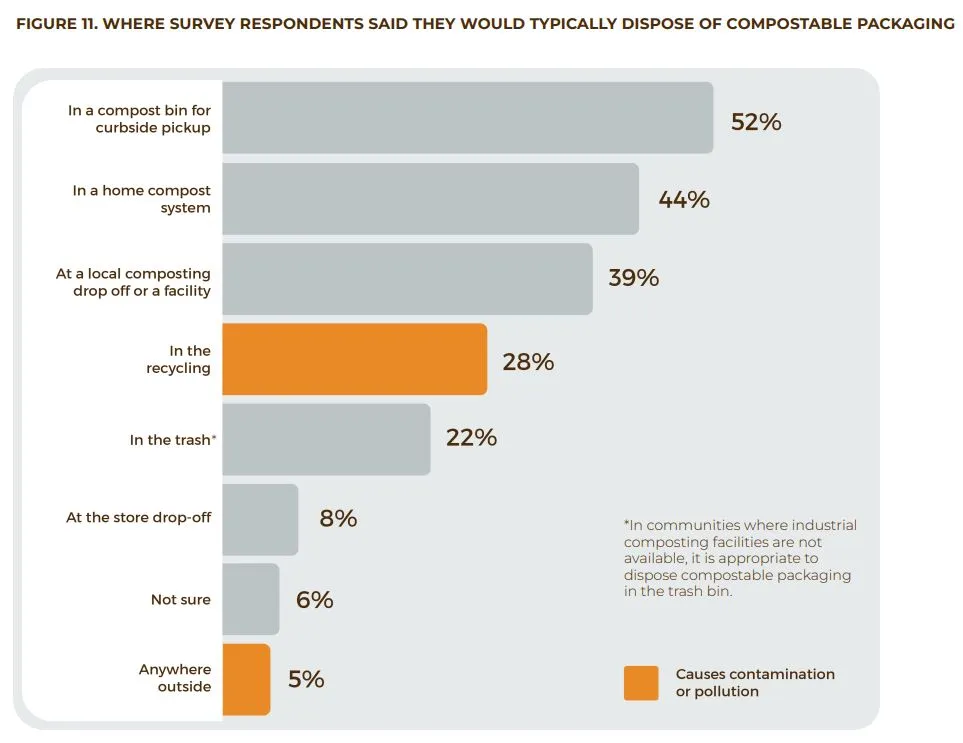

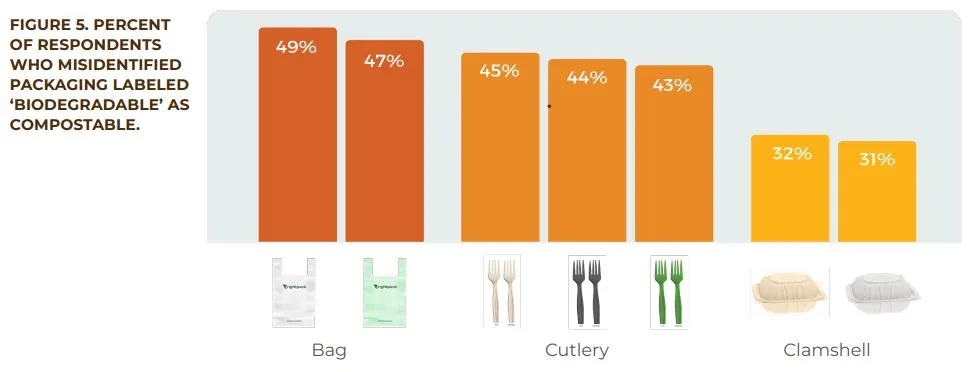

- The survey found that about 49% of respondents had trouble distinguishing between the terms “biodegradable” and “compostable”; up to 50% of respondents thought they could compost packaging labeled “made from plants”; and nearly one-third of respondents said they would incorrectly put compostable packaging in a recycling bin.

- The report recommends solutions to resolve some confusion, including standardizing the terms printed on packaging, implementing better educational campaigns about what should be placed in recycling versus commercial composting bins, and encouraging brands to prominently display on a product’s packaging the home or industrial compostability details.

Dive Insight:

The study is part of the Composting Consortium’s larger body of work to achieve circular outcomes for compostable packaging, especially as more of these items enter the market.

“[T]he volume of compostable materials is steadily increasing, yet confusion around how to identify and divert compostable packaging to the correct recovery streams remains a challenge,” Paula Luu, senior project director at the Center for the Circular Economy at Closed Loop Partners, said via email.

Labeling and design impact how consumers dispose of packaging, the report concluded. Improper end-of-life disposal can result in compostable products ending up in recycling streams or landfills instead of being processed as organics. It can also result in organics contamination, a costly issue that can result in commercial processors rejecting entire loads of organic material.

Contamination is a growing problem as organics programs spread nationwide. Even fiber or some other seemingly compostable materials can act as contamination if they do not fully break down under commercial processing conditions. The issue has prompted some composters, like A1 Organics in Colorado, to further limit their accepted material lists and eliminate all packaging — even if it is labeled “compostable.”

Consumers frequently do not understand the differences in materials that can be composted in commercial programs as opposed to at-home systems. Plus, “compostable” products are “biodegradable,” but the inverse is not always true; biodegradable is a broader term that means materials will break down but not necessarily at the speed needed for successful composting.

The report notes that look-alike products — often plastics — are a problem because they closely resemble compostable products but are not actually compostable. Non-compostable products displaying phrases like “made from plants” add to the problem and lead consumers to believe the items are compostable when they often aren’t, according to the report.

The report also highlights the importance of compostability certification through organizations like BPI and prominently displaying that on packaging labels to improve correct material placement and recovery.

“It is the label ‘certified compostable’ that ensures packaging has met standards and is considered suitable to break down in a composting facility,” Luu said.

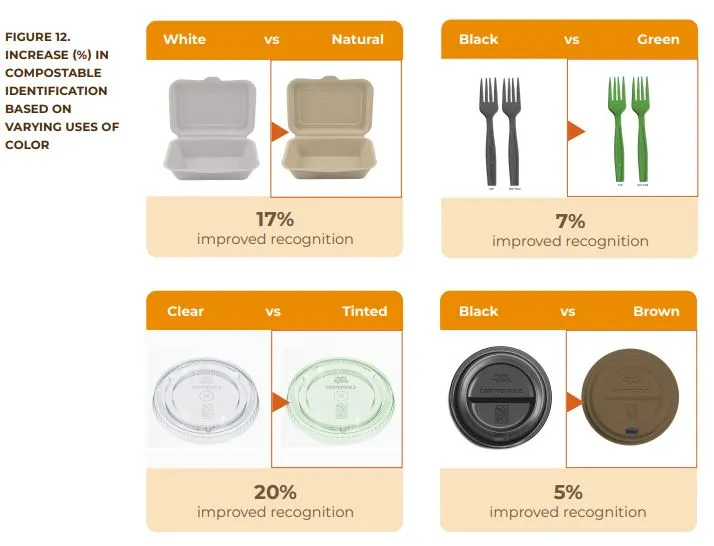

Words, or the lack thereof, aren’t the only element contributing to look-alike confusion. The report shows how product design and color influence consumers’ perceptions of compostability and recyclability. For example, green-dyed service ware might elicit different compostability perceptions than black. Similarly, white clamshell containers could prompt different consumer perceptions than natural-colored containers.

Luu said the consortium hopes brands, manufacturers and policymakers will reference this “foundational” study to advance labeling consistency, advocate for label standardization policies at the local and state levels and reduce contamination both for organics and plastic recycling streams.

“Greater clarity in labeling can help resolve the understandable confusion,” Luu said. “These crucial, initial findings highlight the need for additional, complementary studies.”