While take-back programs for recyclables proliferated in recent years, the same cannot be said for compostable products.

U.S.-based compostables take-back programs are rare, the Sustainable Packaging Coalition confirmed via email. But companies are now exploring the concept as a method that they say could boost consumer convenience, decrease confusion and ultimately increase composting participation.

The volume of compostable packaging entering the market is growing, with a sharp uptick in CPG and retailer use of compostables expected around 2027 and up to a 16% compound annual growth rate by 2032, according to a 2023 report from PMMI and Ameripen.

However, consumer access to composting programs remains low. SPC data shows 19% of the largest U.S. cities have some kind of composting program that accepts some form of compostable packaging, comprising 11% of the total U.S. population. Only 7% of the largest cities have municipally run curbside composting programs that accept compostable packaging, covering 3% of the total population.

While composting access is low, it’s gradually growing, according to a newly released report from the Environmental Research & Education Foundation. The number of compost facilities increased by 55% between 2016 and 2021, it showed.

Operators of mail-in and pick-up take-back programs aim to take the burden off of consumers to figure out proper disposal.

“Take-back programs may be a way for companies to increase the chances for items to get successfully composted while access to composting programs remains limited in the U.S., and for applications where the item isn’t accepted in a green bin, like apparel or e-commerce packaging,” Rhodes Yepsen, executive director of the Biodegradable Products Institute, said via email.

Navigating closed-loop partnerships

Elevate Packaging sells compostables, and for nearly three years it has offered a customer take-back program, according to founder and President Rich Cohen.

Once Elevate's customers, such as food brands, collect 50 pounds or more of compostables, Elevate coordinates for a pickup via a partnership with the Compost Stewardship Institute. Nonprofit CSI, which Cohen founded, handles the processing side, too, through a network of partner composters that will accept the material. Elevate also is working on a direct-from-consumer collection model that it expects to launch later this year.

“I was extremely disappointed to know that the items we're creating largely were not getting composted" prior to creating the take-back program, Cohen said. “Our customers can buy anything off of our website, use it for as long as they need to and when they're done we say ‘please compost it.’ But if they cannot compost it, they can send it back to us,” which he likened to a progressive form of extended producer responsibility.

Multiple recent studies indicate consumer confusion limits successful composting. A report last year from BPI and Closed Loop Partners’ Composting Consortium found that consumers struggle to identify and properly dispose compostable packaging. Nearly half of survey respondents reported difficulty distinguishing between products labeled “biodegradable” and “compostable,” and nearly one-third said they would incorrectly put compostable packaging in a recycling bin.

“The whole world of degradable packaging is fraught with” these issues, said Tom Szaky, CEO of TerraCycle. The company typically creates partnerships with brands or retailers for take-back programs for hard-to-recycle items, of which it has collected more than 10 billion units to date. It began forging partnerships for compostable take-backs about 10 years ago “when biodegradable packaging, or compostable packaging, first sort of came onto the scene,” he said.

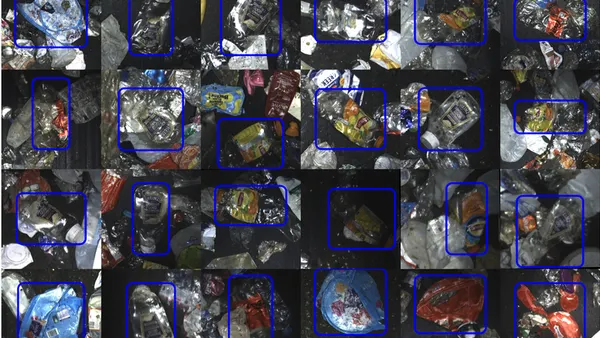

TerraCycle collects compostable chip bags for partner Off the Eaten Path, owned by PepsiCo’s Frito-Lay division, and expects to launch another domestic compostables program soon. Szaky described how consumers can receive a free shipping label to mail in the bags, with the collected material going to TerraCycle’s MRF in Aurora, Illinois. After material consolidation and compliance checks, TerraCycle sends the material to local composters near the Illinois MRF.

TerraCycle conducts third-party reviewed life cycle assessments to gauge the impact of its solutions, according to Szaky, who noted that the environmental impact of landfilling material was greater than the impact of transportation in every instance. The key elements are whether a solution is linear or circular and how big the loop is for circular solutions.

“Once you are in a circular system, you want to make it the tightest of circles,” Szaky said. With the current level of composting infrastructure in the U.S., “the composting circle is a huge number of steps ... It’s a massive loop, even if it is a loop. Recycling is a tighter loop. And reuse is an even tighter loop than that — and that's why we would prioritize reuse, then recycling, then compostability in the journey toward circular systems.”

Elevate still considers compostability the best currently available option to help customers eliminate plastic waste, Cohen said, adding that businesses need to “define a problem properly, then you can solve it.”

But instead of addressing new problems, the industry still is working on the previous problem of “let's provide something, packaging in this case, that protects a product from the moment it's created until the moment it's done being used,” Cohen said. “About 15 years ago someone said, ‘Well, that's great, but I think we also have to expand our problems to be that we don't want that packaging to have any environmental negative impact at the end of its life.’ ... It seems like a very subtle change, but it's completely different.”

Incentivizing composters to accept packaging

Expanding consumers’ access to compostables collection comes with challenges, not the least of which is processor capacity — and willingness to take packaging.

Currently, professional composters “don't want compostable packaging,” Szaky said. “It harms their process and degrades their economics.”

About 200 full-scale composting facilities currently exist in the U.S., many of which are dealing with consumer confusion and contamination, according to a report released last month by the Composting Consortium. Some composters have stopped including compostable packaging on their accepted materials list as a result. But the research concluded most composters found plastic contamination regardless of whether they accepted compostable packaging. In addition, it found that compostable packaging largely degrades as advertised, with eight of nine composters that participated in the study finding no detectable amounts of packaging material in their end product.

Last year, a survey conducted by the Composting Consortium and BioCycle showed that the number of commercial food waste composting facilities that began accepting compostable packaging grew from 58% in 2018 to 71% at the end of 2022.

Take-back program operators view financial incentives as an effective way to attract commercial composting partners.

“When we do a take-back, we have to find composters who are willing to take it and then typically pay them to do that so it offsets that economic challenge,” Szaky said.

The composters that Elevate accesses via CSI also get paid. “The composters are paid, on average, three to four times more than the tipping fees they collect for organic waste,” Cohen said. “They’re very incentivized to do this.”

The idea of improving participation in compostables programs by expanding the existing infrastructure resonates among many stakeholders.

“At this stage in the evolution of the U.S. composting system, investing in recovery infrastructure is critical. We must ensure that composters are supported and incentivized to accept and process food-contact compostable packaging, and that compostable packaging disintegrates well and doesn’t interfere with their ability to sell compost,” said Paula Luu, senior project director at the Center for the Circular Economy at Closed Loop Partners, via email.

Bringing order to the ‘Wild West’

Along with infrastructure improvements, sources expect that greater adoption of EPR laws will drive change in the compostable space, including for take-back programs. Some advocates for additiona regulation of compostables especially target labeling and marketing claims.

During a webinar discussing the new Composting Consortium report’s findings, US Composting Council Executive Director Frank Franciosi said the composting industry needs to work collaboratively with brands and other upstream stakeholders to tackle proper labeling. For instance, better labeling could eliminate confusion over differences between biodegradable, commercially compostable and home compostable products, as well as address non-compostable packaging that mimics compostable versions.

“We have to try and stop it at the faucet first and also advocate for legislation that makes the compostable packaging more uniform and really chastises the lookalikes,” Franciosi said.

Szaky contends that compostability claims on packaging currently are like “the wild, Wild West” because they only need to provide a technical validation, meaning a product degrades in laboratory settings. By comparison, packaging claims about recyclability must align with practical rules, such as the 60% access dictated in the Federal Trade Commission’s Green Guides. But compostables’ easier route might change as more legislation includes them, perhaps in the next two to five years, he said.

“My prediction is that the regulatory environment around making a composting claim is going to become more similar to the burden around making a recycling claim, which is going to make it significantly harder for companies just to claim ‘compostable,’” he said. “When that happens, we would expect a major influx of interest in composting take-back programs.”