The whir of a digital inkjet printer that spits out crisp, vibrant documents in mere seconds is a familiar reference to most Americans. Just as this innovation transformed home and office printing when it replaced legacy tools like the dot matrix printer, industrial-scale digital inkjet technology is now transforming the packaging space.

"It's very similar to a home color printer," said Jim Williams, vice president of sales and marketing at printing equipment manufacturer Kirk-Rudy. "Inkjet technology in packaging is revolutionary."

Digital printing technology is expected to disrupt packaging on multiple fronts, both qualitatively and quantitatively. Leading advantages include the ease and speed of propelling decorative designs from concept to printed image as well as a drastic reduction in waste.

Packaging companies including DS Smith, Georgia-Pacific, International Paper and WestRock are "among the digital innovators" experimenting with digital printing, said Ken Hanulec, vice president of worldwide marketing at equipment manufacturer EFI. Other primary equipment manufacturers include Barberan, Domino, Durst and HP.

On a volume basis, digital printing covers about 2% of the total packaging market’s needs, according to data from consultancy Keypoint Intelligence. The technology is in the early stages for packaging amid a slow transition away from analog systems, but momentum is expected to accelerate. Market research company Smithers predicts that digital will prove to be the fastest growing printing technology for packaging from 2022 to 2027.

"Inkjet is a smaller share of the market, but the value is much higher," said Sean Smyth, print analyst and consultant at Smithers, during an October webinar. "This is why more and more converters are thinking about digital: Because it offers high value-add opportunities."

Digital printing's road to achieving mainstream market acceptance for packaging bifurcates between printed label suppliers and those who print directly onto the packaging medium, according to Keypoint Intelligence analysts.

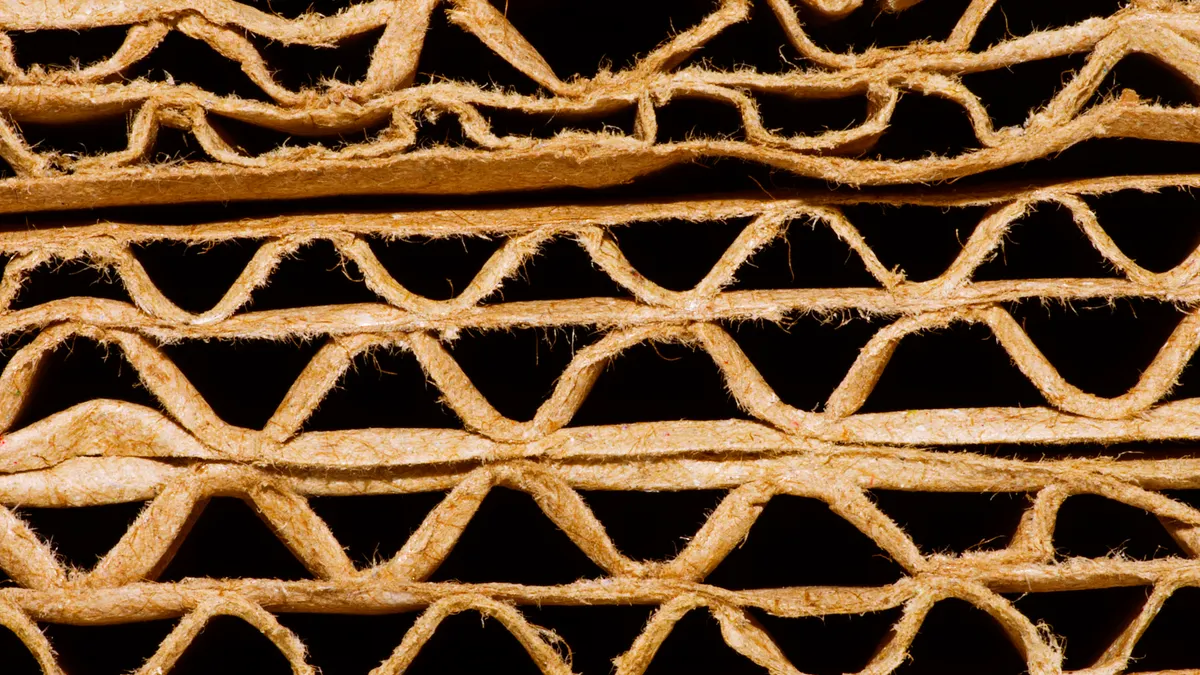

While the digital journey for narrow web labels began in 1994, the use of this technology directly on packaging has only been getting attention for roughly five years. Its use for corrugated packaging first started in 2001 and then re-upped in 2016 with the release of next-generation technology, according to Keypoint analysts. Technology exploration for folding cartons and flexibles is just beginning.

"We're at very different stages of market development as it relates to digital printing," said Jeff Wettersten, vice president of packaging at Keypoint. "In the core markets of corrugated, folding carton and flexible packaging — and if you want to include rigid in that as well — it's really just entering."

Nearly three-quarters, 73%, of converters consider the technology disruptive and transformational for the future, according to a Keypoint survey. As with most innovations, digital printing in the packaging space must overcome early-stage barriers to convince users of the value over tried-and-true systems. Many early adopters and proponents of the technology contend that the efficiency and flexibility gains compared with other printing methods are worth the investment and learning curve.

Converters might initially delve into digital printing to reduce the long-term cost per copy, but "they can and should expand that to drive productivity plantwide," Wettersten said, explaining that better digital utilization aids overall line optimization, thus improving systemwide productivity. Converters stand to achieve a 5% equipment utilization improvement, which "has a big impact on profitability," he said.

"Print is the traditional bottleneck in a converting facility, and if you remove that bottleneck you can streamline both upstream and downstream processes," Wettersten said. "That's where transformation begins to occur [with digital printing]: aligning systems and workflow and enabling new capabilities around responsiveness and flexibility."

Enough on the plate

Methods such as offset lithography, flexography and rotogravure have dominated the packaging printing industry for decades. These processes involve engraving or embossing designs onto the surface of metal or flexible plates — either flat or cylindrical in shape — then applying ink to the plates and stamping the packaging medium.

Depending on the method, different colors must be applied in layers using separate plates. And producing a new design requires the time-consuming and costly process of creating a new plate and switching it out for the old. Often, each print job requires numerous plates.

Digital printing, on the other hand, does not rely on plates. Designers develop the desired image in a computer program and send the digital file to the inkjet mechanism that sprays ink droplets directly onto the packaging medium.

"You're going straight to the press with the file. So as soon as the artwork is approved and signed off on, and it's sent into the machine, you can start printing," said William Barlow, market development manager at Printpack, which uses digital printing for flexible plastic packaging. "You don't have these extra steps and extra costs associated with printing."

Digital equipment generally comes in two different models: web press, in which a continuous feed of packaging material snakes through roll-to-roll machinery to be cut into sections after printing, and sheet-fed, such as those used for some corrugated media.

Web press tends to be less complicated than sheet-fed, said Ryan Fox, corrugated packaging market analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. He said that with sheet-fed "each individual sheet has to be transported, it's thicker, it is open to a wider variety of turbulence and disturbances," and that contributes to differences in print quality between the two machine types. Those factors also add to an approximately 10-times greater output capability with a web press than a sheet-fed version, Wettersten said.

"What we're seeing today is large corrugated companies starting to invest in web presses to totally change workflow," he said. "The impact on lead times is rather eye-opening: You can take conventional lead times of 18 to 20 days for repeat orders down to fewer than five days on a digital press."

While earlier digital equipment often required sending the medium through a printer multiple times to achieve the desired colors and ink coverage, single-pass digital printing emerged in 2016 and is further changing the game, according to Keypoint.

Multi-pass equipment was "very slow and it was running one very big [corrugated] sheet at a time — and that sheet might take several minutes to print," but now single-pass digital equipment is more efficient and more common, Fox said. He estimates that around 60 single-pass digital printers for corrugated are operating in the U.S.

Older, shuttle-based technologies used printheads that moved back and forth over the medium. Modern single-pass printers use fixed heads that drop ink as the medium passes underneath on a conveyor.

"The super high-speed shuttle-based systems have reached their physical limits based on physics and drop placement, accuracy, motion control and just the speed. I literally can't go any faster with a shuttle system," Hanulec said. "Single-pass is such a scalable technology ... We really believe single-pass is the future."

About 80% of the 60 digital units that EFI has installed worldwide are for corrugated packaging, and the other 20% are for signs and displays, Hanulec said.

"Typically the corrugators have a press within every 300 to 500 miles of their distribution radius so they can deliver boxes to the supply chain or their retail customers," he said. "We see an opportunity to put many, many printers in [for] those big players to help them on their mission to go 100% digital."

Much of the digital printing talk centers on corrugated not only because that comprises the largest packaging segment, but also because it's one of the more favorable substrates for this technology. Water-based ink works on porous surfaces, whereas ultraviolet ink lies on top of the surface and works with substrates like plastic. Digital ink gives a different and better look, said Smith Lankford, general manager of the packaging division at printing and marketing solutions company Quad.

Keypoint analysts also predict an "explosion" of hybrid machine uptake. These printers integrate multiple digital and analog printing and converting technologies — predominantly digital and flexo — to leverage each system’s strengths. The digital inkjet printing line could be equipped with one or more flexo stations, for instance. Suppliers including Heidelberg, Kento Digital Printing and Krones produce hybrid systems.

Hybrid options are becoming popular digital entry points for converters who seek greater versatility and automation without a complete commitment to digital. Some converters also prefer the layered benefits of digital inkjet's ease with flexo's coating and embellishment capabilities.

Digital printing technology isn't limited to flat-surface substrates, though. Packaging suppliers traditionally have used silkscreen printing to transfer decoration directly to bottles and cans without labels, but digital inkjet printing is trickling into those spaces as well.

"We understood that the technology challenge was going to be in directly printing on a 3D-shaped container," said Melianthe Leeman, global marketing director for wine and spirits at O-I Glass. The company has operated a digital machine in Europe for about four years and works with Krones to optimize the printing process as needed. A mid-term goal, which the COVID-19 pandemic sidetracked, is to expand digital capabilities to O-I's U.S. facilities.

A key feature is that the equipment doesn't tip bottles horizontally during decoration and rotates the upright containers to allow ink transfer onto all surfaces. "This one actually keeps the bottle in a vertical position. And the bottle doesn't move — the print cage spins on itself. Then you have printheads that are printing the image using CMYK technology," Leeman said.

Stepping up sustainability

Digital inkjet printer suppliers and service providers tout the innovation's sustainability benefits over analog. Largely, they describe gains from eliminating printing plates, which can mean less waste and emissions.

Producing industrial-scale plates that each can weigh hundreds of pounds is resource intensive. While some printers recycle or repurpose analog printing plates — especially the metal ones — many plates are disposed. True tonnage is difficult to quantify due to the variances in each company's printing schedules, but Fox suggested that "millions" of plates become waste each year as they wear out or print designs change.

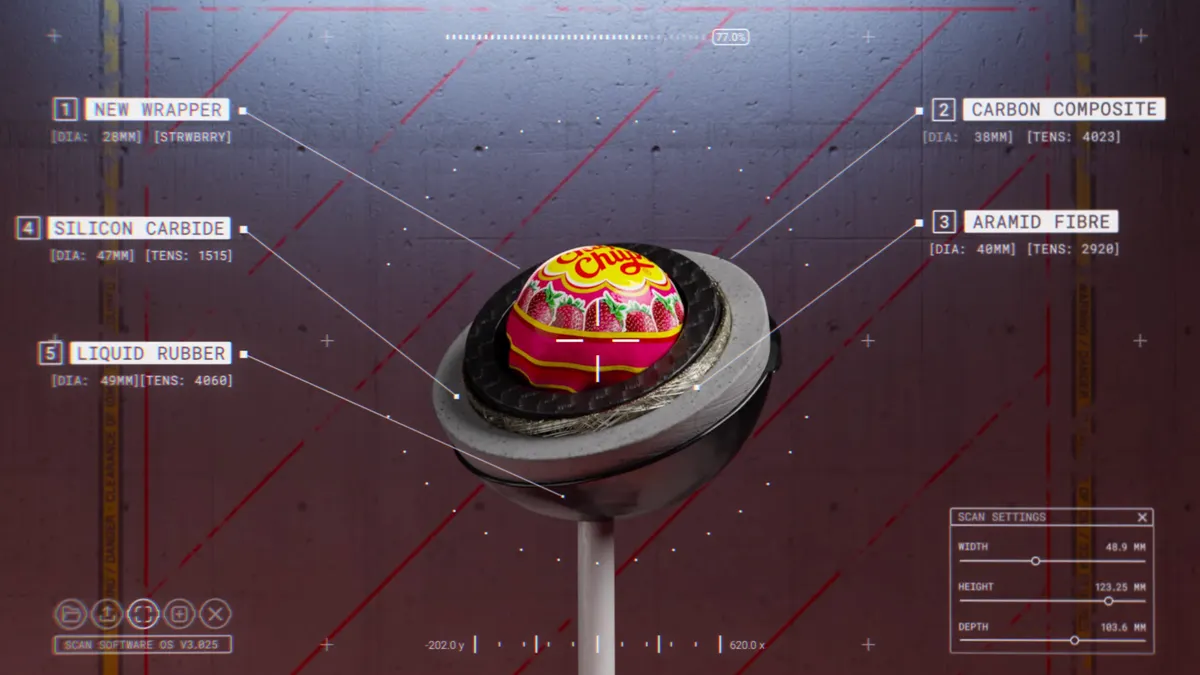

Direct-to-medium printing eliminates extra materials and waste from the additional label substrates. And digitally-printed three-ply cardboard doesn't need to be made with an extra layer specifically for printing, said Robert Seay, vice president of digital print strategy and growth at Georgia-Pacific. "You get rid of one layer of paper. So it's theoretically more efficient and environmentally friendly than what was traditionally the four-ply type of solution."

For bottles, eliminating labels cuts out a substrate and eliminates the waste from minimum order requirements, said O-I's Leeman. "With digital printing, you print the quantity needed in time for the filling campaign, so there is a lot less waste."

On-demand printing lets converters across substrates mitigate overproduction to considerably reduce waste volumes. Plus, users say inkjet's precise ink-dropping technique can reduce waste compared with offset printing.

Other digital inkjet machinery processes, such as curing, are more energy-efficient than on analog machines, thus reducing overall carbon emissions.

"We use LED UV ink-curing technology that uses 80% less energy than some of the heat-based curing technologies,” EFI's Hanulec said, describing it as a “cool-cure technology.”

While UV inks themselves aren't completely recyclable, "there's a way to do some separation" from the fiber during processing, he said.

Implementation impediments and improvements

While the technology use is growing, sources say that mainstream digital printing technology uptake will require overcoming certain impediments.

Retrofitting analog systems is not a feasible option. Thus, companies typically invest in an entire line rather than piecemeal components, which drives up cost. Upfront machinery prices still are high because of the innovation's newness in packaging, and that cost is a leading factor that has stunted more widespread adoption so far, Bloomberg’s Fox said.

On the production side, digital printing is more expensive up to a certain volume, sources say. The cost crossover point varies by company and print job, but sources say generally it lies somewhere in the thousands of impressions.

"A crossover point is somewhere between 10,000 and 50,000 impressions. Once you get longer than that, probably flexo or some of the existing analog technologies have a leg up," Hanulec said. "But we believe that the value proposition associated with digital printing far outweighs the limits of that longer run and that cost per unit. We believe there's going to be a pivot."

Many equipment suppliers and packaging converters consider digital printing more suitable for small jobs or short runs.

"If you were printing 4 million of these [items], inkjet would not be the technology of choice because it is expensive — you use these water-based inks, and the whole process could be expensive in the long run," Kirk-Rudy's Williams said. "Flexography or lithography are designed for long runs."

Defining a short run varies by company. But for many converters, low-volume runs are less than 10% of their overall volume, according to Keypoint analysts, who said “participation in low-volume work is a requirement of doing business to maintain participation in the high-volume business the converter desires.”

In addition, it can be challenging to use digital web press equipment to finish folded cartons, Quad's Lankford said.

"We do have finishing equipment that helps us do the die cutting, and to get it ready to go to folding and gluing," he said. "But it's a little bit more complicated, a little bit slower, equipment. So it's not the perfect fit for long-run production."

On the sheet-fed side, Quad also experienced some equipment challenges with the color process. "We couldn't match enough of the Pantone library to meet customer needs" while using the four-color, sheet-fed digital machine, Lankford said. Conversely, Quad's roll-to-roll equipment uses six or seven colors, which gets the final product closer to the Pantone color library.

"There have been advancements. It has gotten better," Lankford said. "At some point in time ... I believe it'll get to the point where it's competitive with offset printing. But it's just not there today."

Equipment manufacturers continually tweak the machinery to mitigate customer challenges. For instance, Kirk-Rudy's Williams pointed out a wiper mechanism to prevent a common issue with inkjet printers: clogged printheads. A specially cut cloth runs over the heads after a certain number of impressions, eliminating the need for operators to manually wipe the heads.

And unlike home inkjet printers, the industrial models have "microscopic particles of ink, when the machine is idle, flowing through that head" to prevent drying and clogging, he said. Kirk-Rudy offers a proprietary feature so the belt doesn't become covered with ink: a small vacuum that sucks ink particles into a trough.

As digital printing technology improves further and more converters adopt it, the price will come down — as it does with most technologies — and that will spur a greater push toward mainstream adoption, sources said. Converters who haven't yet delved into digital printing generally suggest it's not a matter of if but when, according to Keypoint analysts.

Scaling up has been "a slow haul," but digital business is steadily rising and expected to hasten soon, EFI's Hanulec said. "The time is now for analog to digital to really start to accelerate."

Editor’s note: Read the second installment of our series on digital printing, which looks at how and why packaging companies are using digital inkjet printing to meet customers’ evolving needs.