The Federal Trade Commission will convene a workshop in Washington, D.C., on Tuesday as part of its ongoing review of the Guides for Use of Environmental Marketing Claims — better known as the Green Guides — which have drawn the interest of many states attorneys general.

A public comment period generated input from thousands of individuals and groups, including a collection of attorneys general from California, Connecticut, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Wisconsin.

The FTC first issued the Green Guides in 1992, the AGs wrote, saying that action was inspired in part by recommendations from an AGs task force that noted a need for “uniform national standards for environmental advertising.” They wrote that, today, as states try to address climate change and specific environmental issues, “the value of baseline standards for evaluating whether environmental marketing or promotional claims are deceptive and thus potentially unlawful under consumer protection laws cannot be overstated.”

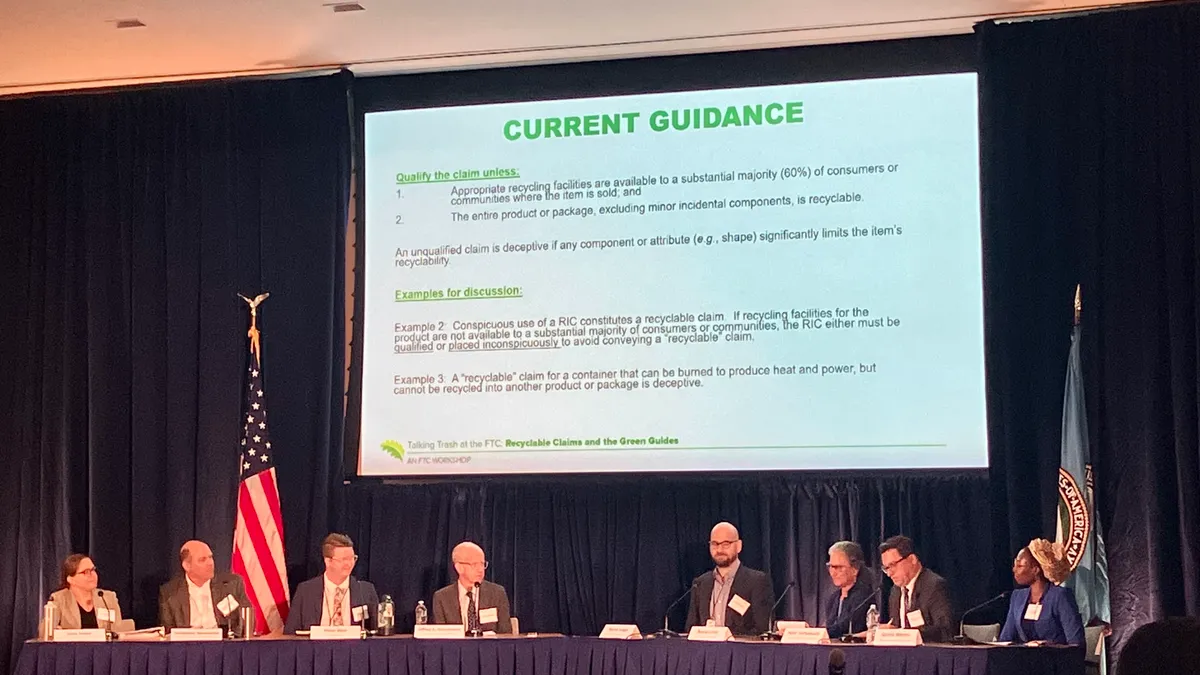

Next week’s discussions will cover the current state of the recycling market, consumer perception of recycling claims and the future of the Green Guides, including analyzing possible changes or updates to ensure marketers can avoid deceptive “recyclable” claims. The state legal leaders said they “strongly support maintaining and strengthening the Green Guides.” These are some of the packaging and waste-related aspects of the guides they weighed in on:

‘Compostable’ claims

The AGs urged an “overhaul” of the compostable claims section “to incorporate not just scientific standards, but also the known practical limitations inherent in composting at scale.”

They wrote that there has been a “substantial expansion” in industrial composting infrastructure in the past decade, “and countless items are labeled compostable, when, for various reasons, they often provide no real environmental benefit over non-compostable items.”

Environmentally conscious consumers may often believe that “compostable” products are superior, while their disposal realities may not be.

While some states have worked to address issues with compostable claims versus degradation realities, “we now call on the FTC to survey industrial composting facilities across the country, specifically mixed-materials facilities, to determine an appropriate and consistent timeframe for the composting of compostable material at an industrial composting facility for inclusion as a standard in the Green Guides,” they wrote.

At a minimum, items should only be labeled as such “when defensible scientific evidence demonstrates that all materials in the product or package will achieve the rate of biodegradation necessary to become finished compost within industrial composting facility timeframes where the product is sold,” they wrote.

Among proposed changes to the guides, the AGs recommended that any item labeled “compostable” must specify whether it is compostable in an industrial composting facility or a home composting pile or device or both, along with meeting certain biodegradation parameters.

‘Recyclable’ claims

The AGs described recyclability labels as perhaps “one of the most widely misused” environmental marketing claims in the United States. To date, they wrote, the FTC’s guidance on the terms has not succeeded in substantially reducing consumer deception or confusion about which consumer items are actually routinely recycled.

Similar to compostability claims, there is a discrepancy between items labeled “recyclable” and those that actually end up getting collected and processed through recycling systems — with many of those products winding up in landfills, as litter or being exported. The AGs also stated that overuse of the label “exacerbates the solid-waste crisis and may actually hinder recycling efforts.”

“We urge the FTC to update its guidance to make explicit that ‘recyclable’ means what the FTC has intended it to mean — and what consumers understand it to mean — namely, that when the consumer properly disposes of a ‘recyclable’ item, it is actually recycled as a matter of course,” they wrote.

For one, they want to set a “routinely recycled” threshold based on established recycling within geographic regions where an item is sold to determine whether marketing an item using an unqualified recyclable claim is permissable. The AGs clarified that they’d like the FTC to set that threshold “as high as reasonably possible to ensure consumers are not misled or deceived” by recyclability claims. D.C., Massachusetts, Oregon and Rhode Island are calling for adoption of a 90% threshold.

“Recycled” should mean that an item is reconstituted into a new product or processed for use in manufacturing or assembling another product, they wrote. Conversion of plastic waste through “advanced” or “chemical” recycling, for instance, should not count as a recycling program at this time, they wrote.

The AGs wrote that qualified recyclable claims ought to state “NOT ROUTINELY RECYCLED—Please check with your local jurisdiction.” And if a product or package’s shape, size or other attribute limits its recyclability, then any recyclable claim would be considered deceptive.

Climate change-related claims

The AGs recommended adding clarity regarding climate change-related claims to the Green Guides, noting that comparative claims for climate change impacts should be qualified and ideally quantified.

They gave the example of a plastic water bottle labeled “carbon neutral.” That would be deceptive, they wrote, because it is unclear whether that claim applied to the production of the plastic, the production of the bottle, the manufacture of the contents in the bottle or the distribution of the bottle.