It can be easy to take gift-giving and gift-wrapping for granted during this festive season, but the traditions are still relatively new social norms.

Toilet paper, Chinese culture, chocolate, Charles Dickens and Queen Victoria all played a key role in the evolution of wrapping gifts in paper. While it had humble beginnings, the market could be worth nearly $25 billion by 2025 according to one estimate.

Anthropologist Chip Colwell, founder and editor-in-chief of the magazine Sapiens, described the act of exchange in gift-giving as a human phenomenon that creates relationships. "I give you something and you feel compelled to give me something in return,” he said.

Colwell said that wrapping gifts in our modern day culture, and those before us, "creates a social meaning, and one of the fascinating facts about paper is that it was not invented for writing, but for wrapping.” This history can be traced back to Chinese culture.

"Chinese royal courtiers gave gifts of money wrapped in paper to form an envelope, and this validates how early uses of paper fit with today's gift giving and gift wrapping,” he said.

Delaware-based Mid-Atlantic Packaging is one family-owned company that has grown to serve this market with stock and custom printed packaging — including bags, boxes and labels.

"The department store tradition years ago was to gift wrap your purchase. This served as both a means to transport your item, but the packaging and gift wrap, whether it was a box or bag was ultimately a branding opportunity,” said CEO Julie Rotuno.

Gifting through the millennia

Long before there were numerous options for wrapping paper, there was no paper at all.

The invention of paper in China was kept secret for years, according to Jerushia Graham, curator of collections at Georgia Tech's Robert C. Williams Museum of Papermaking.

It wasn’t until merchants began trade via the Silk Road, a thousand years later, that paper eventually found its way west. Nonetheless, the earliest papers were made of cloth fibers and not paper as we know it, Graham said.

"The Moors brought papermaking to Europe, and Spain was the first paper maker.” But, it was not until the 8th century when the Italians — who were first to figure out that adding starch to paper made it better for writing — changed the game. In fact, said Graham, the Fabriano company is the world's “oldest continuously-producing paper manufacturer.”

For centuries, in absence of paper wrapping, gifts in Europe were traditionally wrapped in cloth or decorated boxes. According to the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, "In Elizabethan England (1558–1603), elaborate purses were often used to parcel gifts ... often made from knitted silk or silk satin with metallic threads;" and "the box itself was a gift" while the contents such as sweetmeats (candies) or perfumes, were often incidental.

From there, Graham said, "the world of paper evolved dramatically with the emergence of the Fourdrinier machine."

Invented in 1799, its series of hand-cranked metal rollers was perfected by the early 1800s. This changed the tedious vat-based papermaking process forever. By 1809, the Fourdrinier could turn out a sheet 30-foot-wide sheet at a rate of 60 feet per minute.

Still, this was processed cloth paper. Making paper out of wood pulp was an idea that evolved from looking at nature, said Graham.

"By observing how wasps used wood pulp to make their paper-like nest, it was clear it could be done, but cracking the code on chemically removing lignin from wood pulp was an obstacle,” said Graham. “Once that was solved the gates to making big batches of paper were opened and when paired with the Fourdrinier technology, became a paper production game changer."

Chocolate, Scrooge, Christmas and a queen

According to historians, the Christmas holiday and festivities really took off when in 1840 Prince Albert brought the Christmas tree with lit candles inside Buckingham Palace for his wife, England's Queen Victoria.

"As drawings, and later photos of the Queen at Christmas, with her family and gifts set under glowing pine trees were sent throughout the empire, Christmas quickly caught on as a special day and one to make the most of,” said Allie Alvis, curator of special collections at the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library in Delaware.

Around the same time in 1843, the holiday was immortalized in Charles Dicken's "A Christmas Carol." The growing tradition of holiday festivities further instilled seasonal gift-giving in popular culture.

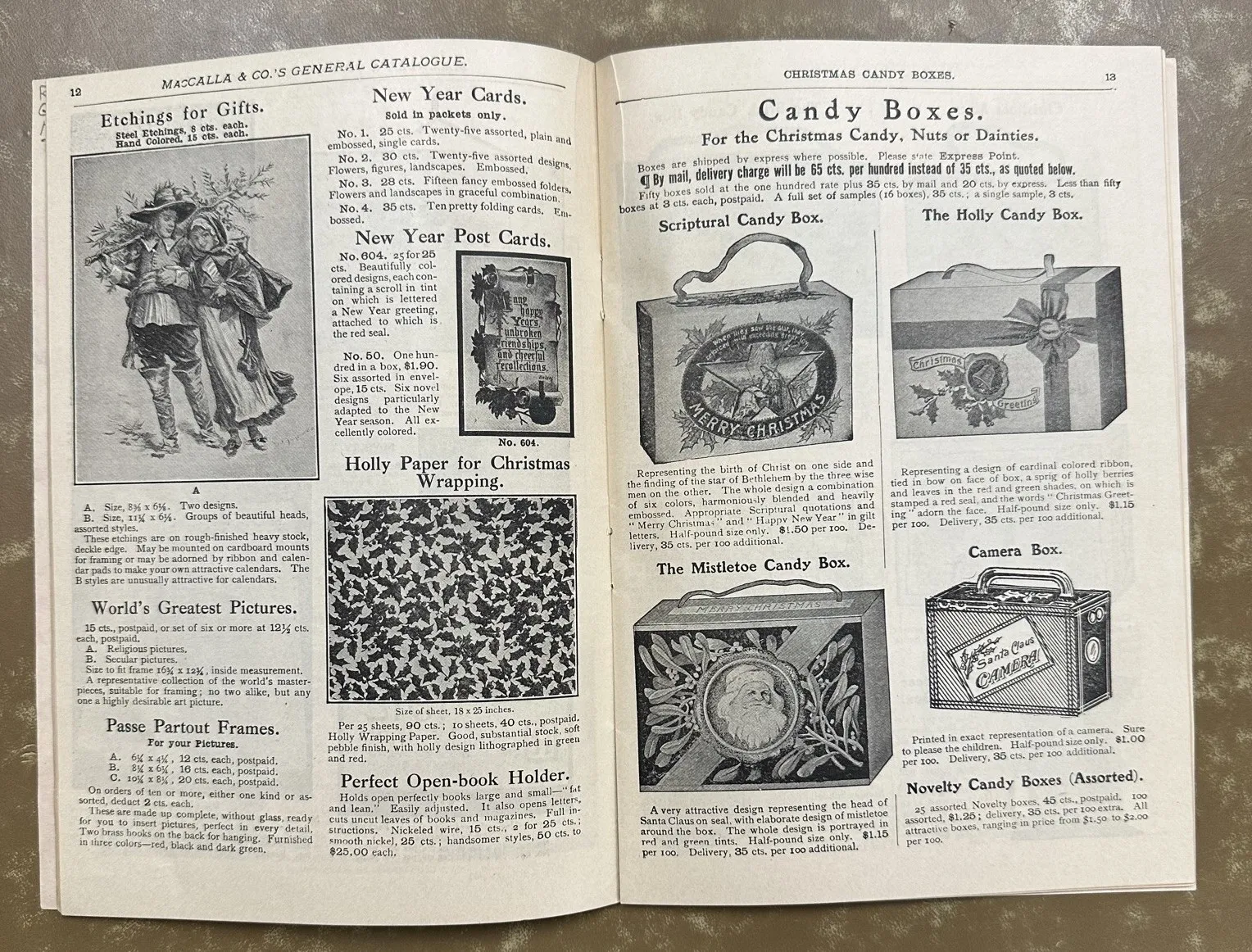

Alvis cited periodicals from their collections, such as the 1911 catalog of MacCalla & Co. which offered holly-printed gift papers for sale, "lithographed in green and red.” Ten of the 18-by-25-inch sheets could be had for 40 cents. Alvis said an 1898 periodical called The Puritan also reported “quite extensively” on the etiquette of gift giving and wrapping.

"In their ‘Ins and Outs of Housekeeping' we read: ‘In this day of pretty flowered boxes, ribbons and colored papers there is no excuse for a slouchy, ragged uninviting Christmas parcel,’” said Alvis. "So, this verifies that even in 1898 gift wrapping for the holidays was an ongoing practice.”

By the end of the century the holiday was an entrenched custom, with increasing use of distinctive holiday papers and cards. Plus, the booming candy market of the late 1800s increased the use of decorated papers and boxes as purposeful packaging.

In New York City, a district known as Cocoa Corners arose, with prominent chocolate makers setting up shop to serve a market hungry for new confections. By the first quarter of the 1900s nearly all the commercial chocolate retailers were using distinctive designs on their boxes to portray quality contents; designs suggesting it was also a perfect gift.

The Puritan, Alvis noted, saw another virtue of this trend: "Today the thrifty housewife saves the cords of gilt and silver thread that tie her candy boxes; the boxes themselves she stores carefully in a closet where she hoards every bit of tissue paper."

For example, the company Huyler's — which became America's largest chocolate maker until the 1960s — featured iconic, pink-wrapped bonbons and boasted the tagline: "A token of good taste." Their advertising text described "smartly fashioned packages that appeal to la femme du beau monde" with images of women gleefully opening the chic candy boxes that projected a feeling of sophistication.

Promotion through packaging prevails

This strategy of pairing advertisements with an appealing packaging aesthetic has only grown since then, leading to a robust market for gift wrapping today.

Mid-Atlantic Packaging, which has been operating for 42 years, now works with boutiques, jewelry stores, retailers food and gourmet shops, e-commerce businesses and others. Rotuno said the majority of their customers are independently owned shops and boutiques, each with a distinctive product or service that want help delivering their message.

This market has stayed resilient, even as parts of it have shifted.

“In the early 2000s, using gift bags, instead of a wrapped package, to present gifts really took off. This affected the gift box, gift wrap and ribbon industry,” said Rotuno. “However, a lot of the independently owned retailers still offer gift wrapping as an additional service. They know that when someone receives a gift wrapped in pretty gift wrap and tissue and tied with pretty ribbons and bows, there is an emotional euphoria experience that adds value to the gift itself.”

Tissue paper, a common part of gift wrapping, is another category that shows how longstanding traditions still persist in today’s market.

As early as the 6th century, according to historians, the Chinese had developed thin toilet tissue from bark and silk, crafted in small sheets, perfumed and placed in boxes that were considered suitable for emperors and their families. It would not be until the early 19th century that a similar thin tissue in large sheets would appear.

“If you said ‘wrapping paper,’ you meant plain brown or white paper tied with string that you just rip off and throw away,” said Alvis. “Tissue paper on the other hand, was a defining element to imparting a special quality."

Alvis said that using tissue paper in gift packaging was seen as a way to add to the special mystery of a wrapped gift, a feature that Colwell agreed remains important today.

"I think it fits with our overarching movement toward more and more stuff. In the industrial age where we have so much available to us, and so much of each thing is identical, we are searching for ways to distinguish them and make them unique,” he said. "But, when you wrap it that makes it special to create the human connection."