Dive Brief:

- Coming on the heels of announcing global agreements and a joint venture with Indonesia-based investment company Sintesa Group, J&J Green Paper says it is eyeing Arkansas and California as target areas to set up the first U.S. plants to manufacture its coating for paper and fiber packaging.

- JJGP’s organic, plastic-free barrier, which it calls Janus, is primarily derived from rice plants, along with some sugarcane and calcium stearate. JJGP touts it as a fully biodegradable and backyard-compostable alternative to conventional polyethylene fiber packaging barriers.

- Thus far, Janus has been produced in sample-sized quantities for testing purposes. JJGP executives are working to secure numerous additional funding and production agreements to scale commercial production, said President Rick Bulman.

Dive Insight:

JJGP stems from research that began about 10 years ago. It all started “as a project to find a better pizza box and coffee cup, which basically evolved into a barrier. That's the key to everything: a barrier,” said Scott Segal, founder of JJGP and Janus inventor.

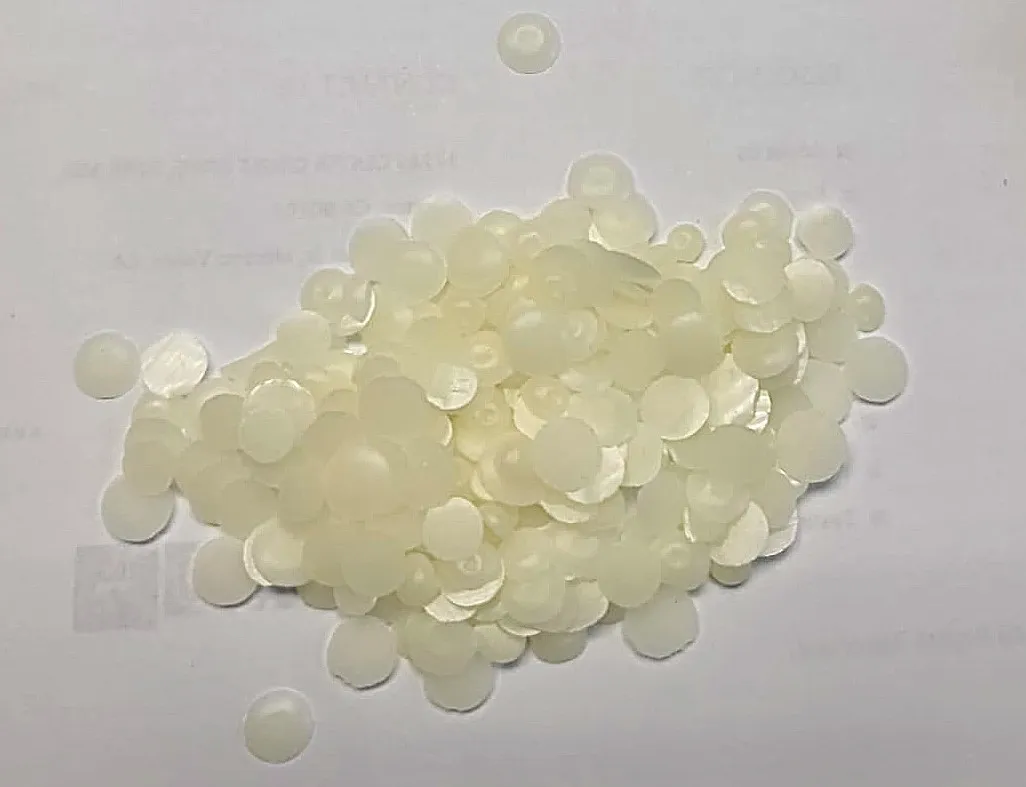

The Delaware-based company’s business model is to expand Janus production via both licensing agreements and joint ventures. It is currently developing nearly two dozen facilities for exclusively manufacturing Janus in Indonesia, India, Thailand and China, and negotiations are underway for an additional 30 plants. Each facility has the capability to produce 25,000 metric tons of Janus pellets annually. JJGP received a patent for the product in March 2022, and it has earned a label designating it part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s BioPreferred Program.

JJGP also recently entered an agreement with Mc Papers Argentina, which supplies fiber products to fast food restaurants in Latin America. Under this deal, the Janus will be used for producing food and beverage packaging such as hamburger wrappers and french fry holders. Janus provides a chemical-free alternative to PFAS, the “forever chemicals” currently coming under fire, which often have been used to improve fiber food and beverage packaging’s resistance to grease and moisture.

“We are building manufacturing facilities logistically near where the rice production is in the world to be able to shorten our transportation costs,” Segal said, adding that the business partners in the deals are the facility operators. “Delivery of the product is where our clients and potential clients are. We've spent a few years developing an enormous client base with letters of intent and directives for how they would like to transition into the product as we progressively scale it up.”

Segal said deciding where to establish production in the U.S. primarily relies on two factors: where rice grows and where paper is coated. He said California and Arkansas are two of the nation’s top rice-producing areas, and many paper mills are located in the Southeast and Northwest.

“The majority of our product comes from — we use the word ‘waste’ — the remnants of rice harvest: the husk and the shell,” Segal said. “We blend it all together in our formula of the three [components], pelletize it and then that's what's delivered to the facility that would be coating the paper for the converters to make into the end products.”

More companies are working on projects to transform agricultural waste into materials that can be used in packaging as pressure increases to find alternatives to fossil fuel-derived plastics. For instance, Dow announced last month a project to create a bio-based plastic from corn crop waste; it can be used for packaging and other plastic products.

Companies are also increasingly focused on developing packaging and barrier solutions that are fully biodegradable and compostable, especially as more composters eliminate packaging — even items labeled compostable — from organics programs because it doesn’t always break down and therefore becomes contamination. JJGP says Janus is certified compostable by the Biodegradable Products Institute.

Converters would need to slightly modify their machinery to use Janus instead of polyethylene-based coatings. Polyethylene melts at a much higher temperature, Segal said, and remains as a coating layer on top of paper. However, he said Janus absorbs into the paper fibers and “becomes an integral part” of the paper.

“If you took a piece of paper that was coated with the Janus compound and put it under a microscope, you would see it intertwined with the fibers of the paper,” he said. “Not only does it give it a tremendous barrier, but it increases the wall strength of the paper.”