Dive Brief:

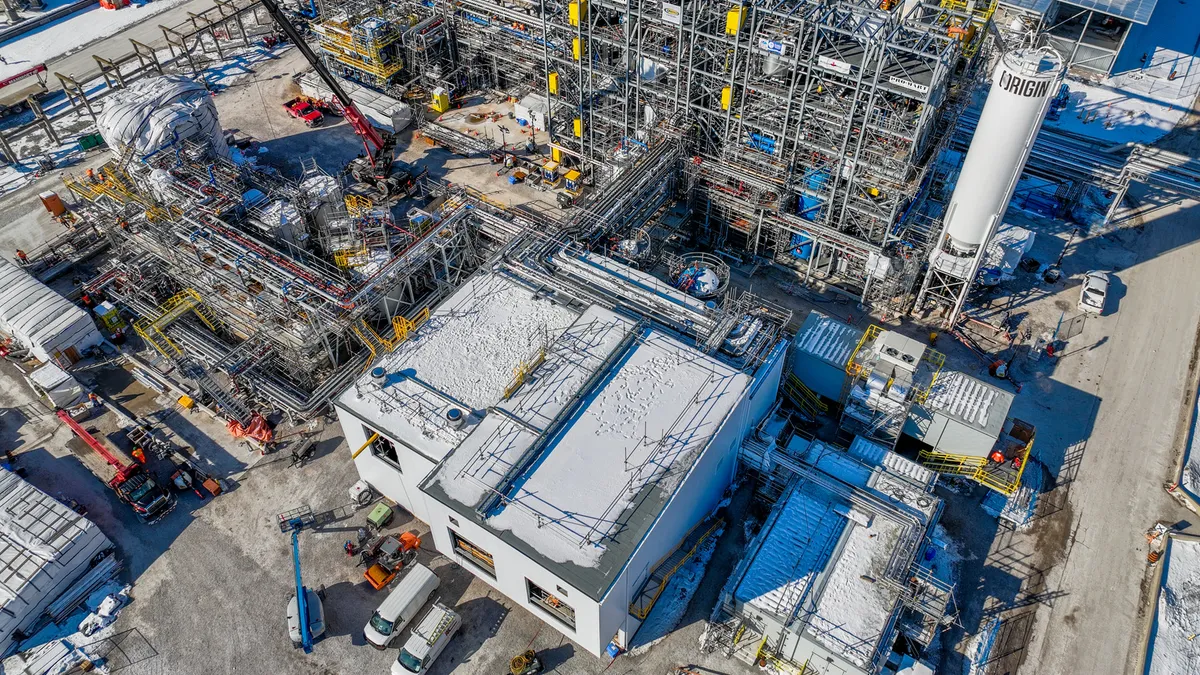

- Origin Materials recently started up its first manufacturing facility in Ontario, Canada, calling it the “world’s first commercial CMF plant.” The chloromethyl furfural it produces is an intermediate component of PET plastic used for packaging.

- The facility transforms non-food biomass, such as pulp mill residuals, into CMF and other materials like hydrothermal carbon instead of using fossil fuels as a feedstock for the plastic.

- “We expect that our material at a fully developed commercial scale is going to have a lower carbon footprint than even a recycled PET,” said John Bissell, co-founder and co-CEO of Origin Materials.

Dive Insight:

Origin Materials went public two years ago via a merger with special purpose acquisition company Artius Acquisition. Nestlé Waters and PepsiCo were “significant investors” and also forged purchase agreements with Origin, said Bissell, adding that the company currently has more than $9 billion worth of contracted demand. Beyond food and beverage packaging, Origin’s materials can be used for manufacturing a variety of products including polymer fibers for upholstery, carpeting and apparel.

The quality of the end PET is the same as if virgin resources were used, Bissell said, but the carbon footprint is lower. Much of the carbon benefit stems from using biomass feedstocks to trap carbon.

“If the materials weren’t being used in our process ... they’re just going to decompose, and when they decompose they turn into CO2 and go into the atmosphere — or they get burned,” Bissell said. “When you use it in our process, that carbon instead of going to the atmosphere gets locked up in our materials. And that's where that carbon benefit comes from.”

Feedstocks include wood processing residues and agricultural residuals like corn stover: the stalks, leaves and husks that remain in a corn field after harvest. Other companies are also finding value in using agricultural residue to create packaging, such as Dow and New Energy Blue’s agreement to create ethylene for polymer production from corn stover as well as J&J Green Paper’s rice-derived barrier coating.

“There's plenty of residuals around, so that gives us all the feedstocks that we need for now — for a long time probably,” Bissell said.

Polymers made with Origin’s materials exhibit the same recyclability as other items, according to Bissell — they’re simply made in a different way. Working with new types of molecules also allows Origin to unlock easier at-scale creation of new fossil fuel-free polymers, such as furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA), from CMF, he said; this also supports easier recycling.

“FDCA tends to have higher barrier properties than just straight PET or polyester, which is great for some of the higher performance applications in food and beverages,” he said. “It's more cost effective, it's easier to process than a multi-layer film and, probably most importantly, multi-layer or multi-material packages don't recycle; so by using an FDCA-based polyester, you can get a material which [can be] recycled.”

However, more testing is necessary to ensure performance at scale in real-world systems.

“FDCA is something we’ve always had on the slate as an interesting product, but we've gotten a lot more feedback from customers in the last couple of years that they want it sooner rather than later. That affects our plans,” Bissell said.

While Origin isn’t offering a firm date for when its new plant will be fully ramped up, Bissell noted the company is giving itself six to 12 months to get that facility to full capacity.

Last year, Origin Materials began constructing its second facility in Geismar, Louisiana. That plant will be larger than the initial facility in Canada and capable of processing 1 million tons of biomass annually. The company anticipates operations will begin at the Geismar plant in 2025.