Food brands have historically been in the dark about what exactly happens along a product’s journey from manufacturer to storefront. Now, more are seeking insights by including a certain type of sticker on their packaging.

Radio-frequency identification has long been popular in retail and transportation logistics, said Randal Dunn, director of customer success at RFID manufacturer and supplier Zebra. “But food is right on the coattails of those two industries. And it's going to be way bigger than either of them.”

The food and beverage sector’s interest in RFID stems mostly from waste and safety concerns. In 2026, new traceability rules from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration will kick in and add extra motivation for the latter factor. Because grocery products cycle through the supply chain faster than other categories, such as apparel or home goods, the RFID devices used to track them would potentially have shorter lifetimes. Questions about complementary packaging choices and recyclability are becoming more relevant as a result.

The Walmart effect

According to the RAIN Alliance, an industry association of RFID manufacturers, 20 billion RFID tags certified by the organization have been consumed worldwide as of 2020.

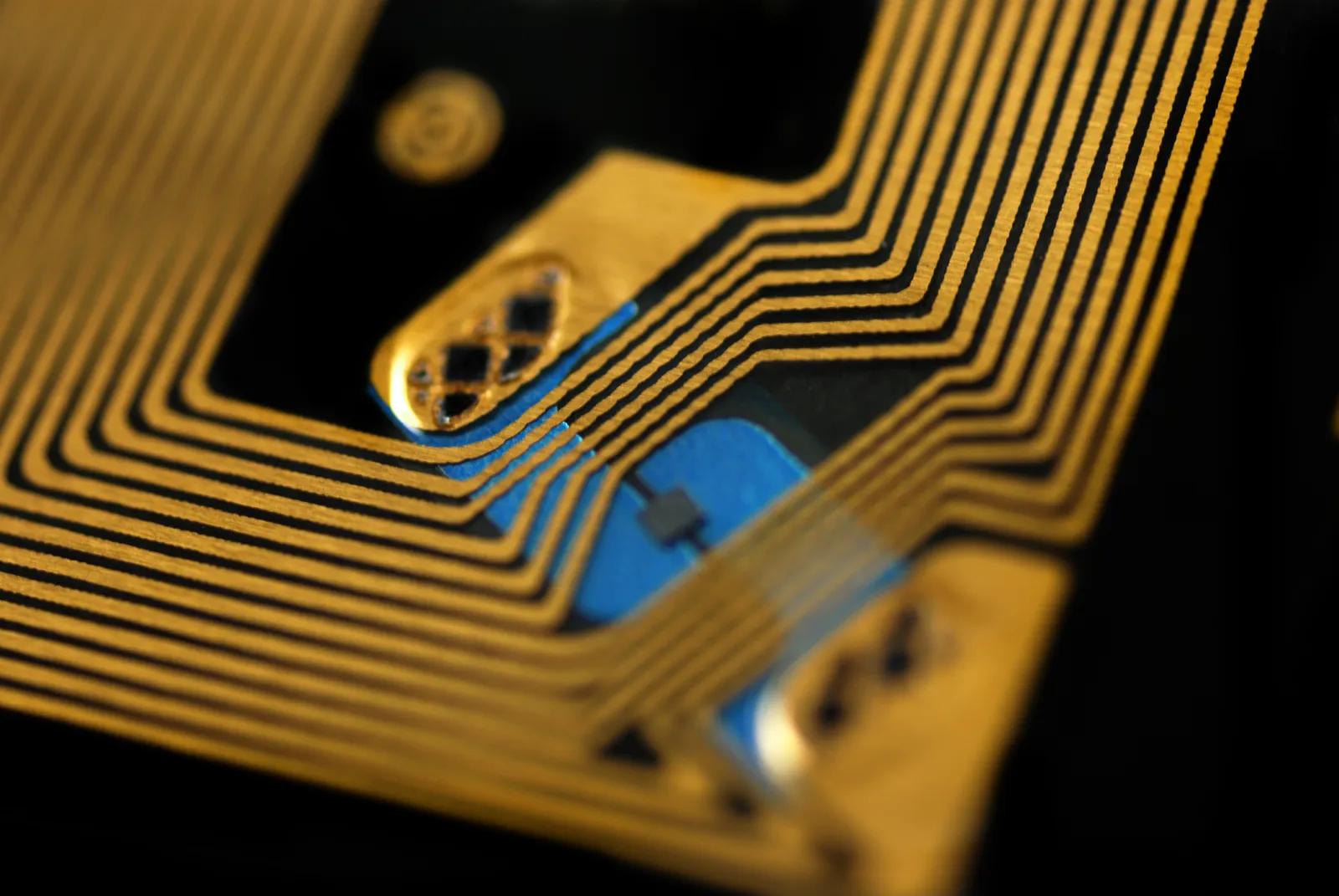

These stickers — adhesives with small chips holding data about the item it’s stuck to — are the first half of an RFID system. The chip can come with a battery to constantly broadcast the embedded information, but the more common design relies on a chip that only transmits its contents when activated by a scanner. The scanners initiate an information relay and the frequency they emit powers individual chips to return a radio wave carrying the item’s information.

The time it takes for RFID to scan an item is at least an order of magnitude faster than with barcodes and doesn’t require line of sight, said Jon Gregory, director of community engagement at GS1, a supply chain standards organization.

Walmart, which was an early and ardent fan of barcodes, has since turned its attention to RFID as a way to improve inventory management. After a brief trial run with the technology in the early 2000s, the company started requiring apparel suppliers to implement RFID in 2020. As of September 2022, all toys, home goods, electronics and sporting equipment packaging also had to be tagged. In the years since Walmart first experimented with RFID, and overall industry adoption increase, Dunn said the cost has dropped “significantly.”

Walmart’s requirements don’t extend to food products, but sources say food suppliers have their own reasons for being interested in RFID and might benefit from the wider recognition of the technology that the retail giant ushered in.

For one, the tags can help cut down on waste, said Bahar Aliakbarian, senior director of research and development at Michigan State University’s Axia Institute, a lab founded with Dow Chemical funding that tests real-world RFID tagging and scanning scenarios. Since retailers with RFID-tagged inventory can learn on command how many of a given item are in stock, grocery stores and other retailers can adjust perishable product orders accordingly.

Supply chain participants that scan RFID-labeled deliveries contribute to the track record for each tag. These detailed histories play an important role in monitoring food safety, which is another reason why some sources see RFID as a clear option for the upcoming FDA requirements.

Once a contaminated batch is identified in the supply chain, any retailer, supplier or producer who might be affected can check their inventory history.

Chipotle, a company fined by the FDA for foodborne illness in 2020, introduced RFID-tagged distribution to manage quality monitoring and emergencies in Chicago restaurants in 2022. The pilot program is now expanding nationwide. More than half of the top 27 food service companies are looking into RFID for similar reasons, said Gregory.

Room for improvement

Upcoming federal requirements could provide a further incentive for retailers that aren’t already interested in this feature to track their packaging and products. The FDA Food Safety Modernization Act directs harvesters and manufacturers to assign traceable lot codes and other relevant pieces of information to their products. Individual item data will accumulate as stops on the supply chain make mandatory contributions to each item history. Foods ranging from soft cheeses to salmon to cantaloupe have to meet the standards by Jan. 20, 2026.

The law doesn’t require the relevant industries to use RFID, but sources view it as a logical option. In some cases, food products might carry RFID on individual items. Dunn doesn’t see this tactic carrying over to individual produce items. Instead, for example, a cardboard box of watermelons could be the more logical place for an RFID device.

Food companies looking at RFID because of the FDA policy or other motivators now have better trackers to work with than when Walmart started its experimentation. When too many tags are clustered close together, interference can keep scanners from picking up on chips in the middle, Aliakbarian said. Scanner sensitivity has improved, however, and some chips operate on dual frequencies to avoid groups of identical signals.

Packaging choices also help determine RFID success. In the short list of preliminary questions Zebra asks a potential customer, one is about where there is space for a tag that avoids interfering with the branding — an inquiry that sometimes ends with packaging needing to change to accommodate the sticker. Another is about what the packaging actually consists of. Aluminum and water, the notorious enemies of radio waves, interfere with RFID reading. “Metal is not RFID’s friend, and neither is liquid,” Dunn said. New tags can surmount those problems, albeit at a higher cost, Aliakbarian added.

RFID adopters also have new standards to guide what tags say. The tracing requirements in the upcoming FDA rule raised questions about what RFID chips need to communicate and how to make sure each participant understands the information.

Last year, GS1 issued updated standards on how RFID users could structure information like batch lots, weights, expiration dates and more. The same standards called for critical product information to be stored on the chip rather than on any cloud-based software. That way, companies don’t need compatible data centers or subscriptions to see information on the same chip, Gregory said.

As improved RFID technology or a uniform way of sharing its embedded data draws more brands to the tracking method, manufacturers will also have to figure out what recyclability looks like. RAIN Alliance recently reported that regulations across the world don’t explicitly address how e-waste from RFID systems should be managed.

“I think that's probably one of the really big questions right now,” Dunn said. “I'd be lying to you if I said it's all been solved already.”

Each sticker — which in Aliakbarian’s lab, are typically between three and eight square inches — holds a radio antenna and a chip, the two components that would need to be broken down and reused. Some packaging providers might navigate reuse by boosting RFID durability: the manufacturer Checkpoint Systems made what it says is a heat and water-resistant tag for McDonald’s France to integrate into reusable containers. Otherwise, dissolvable adhesives and even paper-based antennas are in the works.

Designing recycling systems could be complicated by the lack of a universal tag, in part because each item’s tag may need to be customized for the environments it will move through. “It is possible that if you change one or two parameters of that environment, the RFID could not work. That's one of the biggest challenges of RFID,” Aliakbarian said, “but the technology is growing fast.”